The Durham Boat: Workhorse of Early American River Freight

Testimony by some historians via their interviews (History of Bucks County, by W.W.H. Davis, 1905 and J.H. Battle, 1887) indicate that the first Durham boat was built by Robert Durham on the river bank near the mouth of the cave at Durham, circa 1730. All of this is hearsay evidence that has been passed down via the generations. Robert Durham was stipulated to be a boat builder by trade in certain papers left by B.F. Fackenthal Esq., a native of Durham who indicated that he was told by his grandfather that Robert Durham was the first builder of a Durham boat in Durham. Other sources attribute claims about Robert Durham to the Durham blacksmith Abraham Haupt in the 19th Century. Some folks conclude that Robert Durham worked at the Furnace when the first boat was built. There is no hard evidence for any of this. Historian Richard H. Hulan pointed out that no physical record can be found of a Robert Durham. If he was employed at the Durham Furnace it would be very unlikely that an English foundry man had either the skills or the depth of tradition necessary to invent, build, and give his surname to the boat that was to become the primary shallow draft vessel for round trip commerce on the Delaware River prior to steam.

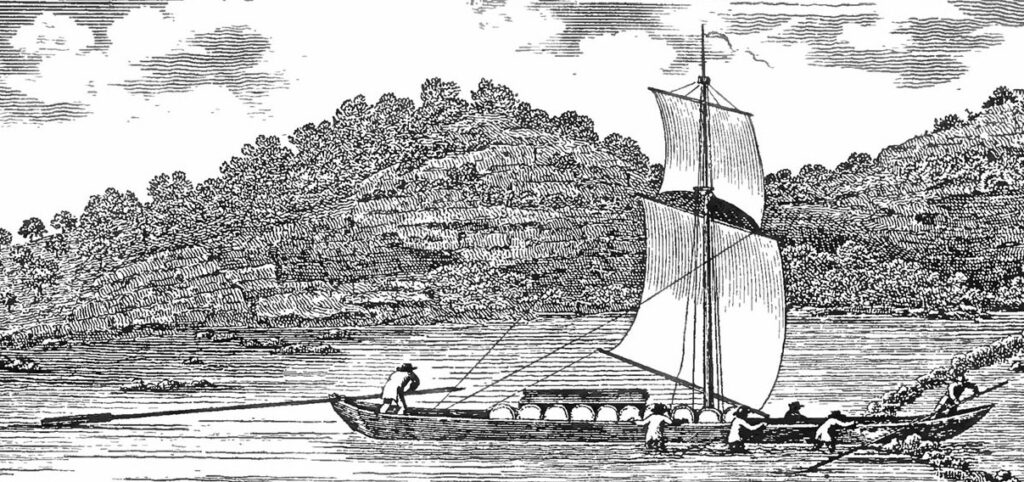

What is known is that the Durham Boat was double ended (sharp at the bow and stern), flat bottomed, up to sixty-six feet long, six feet wide, three feet deep, and drew but twenty or so inches of water when fully loaded. It was propelled upstream against the current by setting steel tipped poles into the river bed, the other end against the boatman’s shoulder who walked from the bow to the stern of the boat. Oars were used travelling downstream in the center of the river, and to cross the river say at Bristol. A mast and sails could be mounted if the wind was favorable. A crew of three to six men was used per boat. A Durham Boat could make the trip from Durham to Philadelphia in one full day. Depending on the size of the boat, it could carry ten to seventeen tons of cargo downstream. The return trip was more arduous as it had to proceed against the current, and upstream capacity was only two tons or less. Much muscle was needed by the boatmen to pole the boat back to Durham.

At one time a fleet of hundreds of Durham boats carried freight on the Delaware giving employment to several thousand men whose job it was to move cargo down the river to Bristol and Philadelphia. Durham boats were used and known by that name on other rivers in the American colonies including the Susquehanna, Mohawk, St. Lawrence, and others.

Durham boats were commandeered by George Washington and used to carry his army across the Delaware River at a spot now known as Washington’s Crossing, PA in order for his troops to surprise the Hessians at Trenton on Christmas Day, 1776. (See links below.)

At one time a fleet of hundreds of Durham boats carried freight on the Delaware giving employment to several thousand men whose job it was to move cargo down the river to Bristol and Philadelphia.

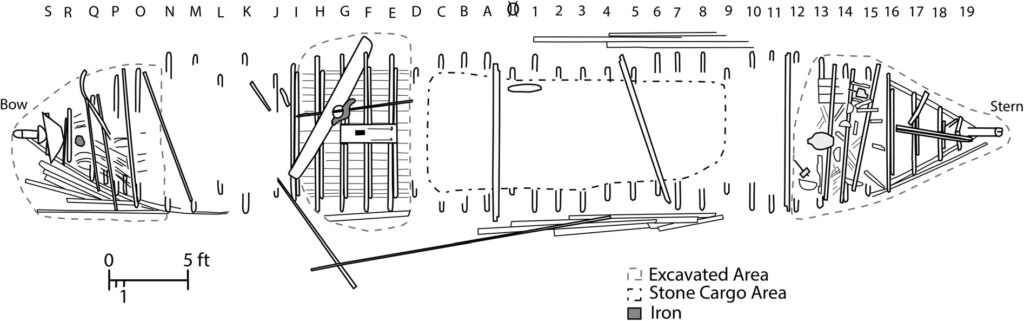

Hulan discussed the so-called “Batsto Boat” that was found in a New Jersey pond when it was drained in 1957. He claims that the Batsto Boat can be dated concurrent with the Batsto Furnace (which ceased iron production in 1848) and that the functions of the craft was the bulk transportation of iron ore. He ties the Batsto boat quite neatly in with the Durham boat which was used for a similar purpose, the transport of heavy iron product downstream. Yet, the Batsto boat had a different shape from the Durham boat (shorter and wider). Although used similarly, the two boat types may not have had a direct relationship in their development.

The Batsto Boat of Batsto Village, New Jersey, has been described as a Durham boat, but its length, the ratio between length and beam (43 ft. [13.1 m] long, 10 ft. [3m] beam, and 30 in. [76.2 cm] deep), and its heavy keel and keelson do not conform to most historical descriptions of Durham boats.

– Ford

Hulan thinks that we should direct our attention to the working boatmen and boat builders on the river, and at that time the Swedes and Finns were those people. The Durham Furnace came into blast (began to make iron) in 1728 and it needed to move product then and not later. Remember that there were no residents in Durham in 1728 just waiting to go into the business of hauling iron product to Philadelphia much less a fleet of boats. However, the Swedes and Finns had been on the river for ninety years and they had been using the waterways for the transporting of people, furs, grains, flour, and tobacco over the same waters. By 1728, the year the Durham Furnace came into blast there were dozens of Swede/Finnish family businessmen whose sole purpose was boat building and transport. Other ethnic groups had seafaring/boat building backgrounds, but the Scandinavian people had been building similar boats to the Durham boat in their native countries for centuries, and according to Hulan, no such similar boats were to be found in the history of the English or Dutch. They were masters of deep water vessels and not these smaller and light drafted boats.

The two models that were made for centuries in Scandinavia were the “Church Boat,” and the “Rapids Boat.” The boats were used in lake waters and in river waters in Sweden and in areas that carried a great number of immigrants to Pennsylvania. These new people oriented their farms and their churches to the existing rivers which, prior to roads, was their only method of transportation. It is also noted that the old iron industry in Sweden was greatly analogous to that found in Durham, one that had to move its product from relatively isolated furnaces on shallow streams down to deep water ports or areas of centralized populations. It seems axiomatic that the water people would employ the same technology used in Scandinavia in their boat building here in America. That boat style was long, narrow, double ended, and operated by minimal crews using poles and oars. Why reinvent the wheel or boat in this case? Are then the Durham boat and the Batso boat evidence that Swedish technology was the causative factor of this design and not the mythical Robert Durham?

It is evident that the form of the Durham boat could be found in rivers all over the Eastern seaboard where they are shallow and sometimes rapid. In other places they were called Keelboats, Mohawks, Schenectady boats etc. but usually all attributed, in general, to the Durham boat style and the Delaware River. The form of the boat was simply the best form to be used to move cargo up and down the extensive, large and occasionally shallow rivers. Hulan concluded that the Batso boat and the Durham boat were born of Swedish or Finnish ancestry. He further dismisses the notion that the boats were an adaptation of the Indian canoe though concedes that the Indian canoe double ended style is equally adapted to the shallow rivers and steams of North America.

The Durham boat style came into disuse with the advent of canals where yet a different type of construction and style was used to carry freight. The Canal Boat went out of service because of improved roadways and the invention of steamboats and steam engines used on railroads.

Sources

Ford, B., Caza, T., Martin, C. et al. 2018. Durham Boat – Defining a Vernacular Watercraft Type. Historical Archaeology 52, 666–683.

Hulan, Richard H. 1986. The Batsto Boat: Evidence of Delaware Valley Swedish Technology. In The Challenge of Folk Materials for New Jersey’s Museums, pp. 63–69. Museums Council of New Jersey, Trenton.

Excerpts from Navigation on the Upper Delaware

By J.A. Anderson Of Lambertville, N.J.

Read before the Bucks County Historical Society At Doylestown, PA, 1912

We now come to a particular consideration of the most important and interesting feature of the transportation methods of the Upper Delaware. This is found in the craft known as the “Durham Boat,” which, until the canals came into use, was the sole means of moving commodities in both directions on the river between Philadelphia and points above tide.

This boat was well known on the Delaware for more than a century, for, even after the building of the canals, it was used on them as well as on the river to a considerable extent. The local histories give little precise information respecting the form and the method of operation of this important means of transporting the commerce of the upper river. To the writer’s own recollection he has been able to add much of interest gleaned from various sources. Much information was obtained from men who had known something of the boat, as well as from some who had operated it.

Of the latter, the one to whom the writer was most indebted was the late Wilson Lugar, of Lumberville, Pa., who, at the age of seventy-eight years, retained a remarkable recollection of details of the construction and operation of these boats. In his “History of Bucks County” General Davis states that the last trip of a Durham boat to Philadelphia was made by Isaac Van Norman, in March, 1860. Mr. Lugar stated that he, himself, made the last trip to that city, with a Durham boat, in 1865, with a load of shuttle blocks, and that the boat used on that trip was the last used on the river.

It is frequently stated that the Durham boat was modelled after the Indian canoe. Both were pointed at both ends, but, in other respects, there were marked differences. In fact the name “canoe” has been applied to a variety of dissimilar craft.

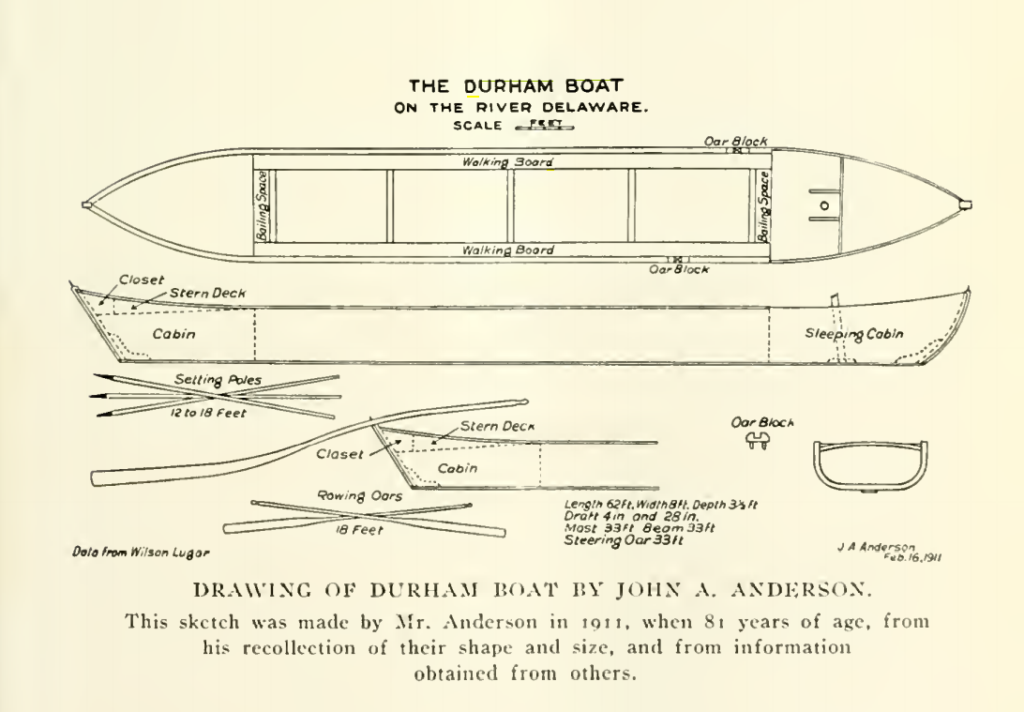

In section the sides of the Durham boat were vertical, for the most part, with slight curvature to meet a like curvature of a part of the bottom which, for the most of its width, was flat. Lengthwise, the sides were straight and parallel until they began to curve to the stem and stern posts, at some twelve or fourteen feet from the ends, where the decks, fore and aft, began, the rest of the boat being open.

The partly rounded form of the hull was preserved at the ends, instead of being hollowed, as was usual in the Indian canoe. Perhaps the craft most like the Durham boat, in general shape, would have been the “dug-out,” a log hollowed out and pointed at both ends, with the bottom and sides slightly flattened.

The ordinary length was sixty feet, although shorter boats were built, and, in some instances, the length was extended to even sixty-six feet, with sometimes a foot or two added to the ordinary width of eight feet. In other localities where the Durham boat was introduced some variations in dimensions were made to suit the local conditions.

The usual depth, from top of gunwale to the twelve-inch keel plank, was forty-two inches, with additional height at the ends of some ten inches, this and other minor features depending upon the fancy of the builder. The draft, light, was from three and a half to five inches, and loaded about twenty-eight inches.

The boat sixty feet long would carry, down stream, one hundred and fifty barrels of flour or about six hundred bushels of shelled corn. Some of the largest boats built would carry twenty tons, although the load for the ordinary boat was from two to five tons less. The load, up stream, was about two tons.

On the Delaware the crew usually consisted of three men. On some of the more difficult streams more were needed.

The movement down stream was by floating with the current. with the aid, when necessary, of a pair of eighteen foot oars. Moving up stream the boat was usually propelled by “setting poles,” twelve to eighteen feet long and shod with iron. On the thwarts was laid, on each side, a plank twelve inches wide. On these “walking boards” members of the crew, starting at the forward end, with poles on the river bottom and top ends to shoulders, walked to the stern, pushing the boat forward. While they rapidly returned to repeat the process, the captain, who steered, used a pole to hold the boat from going back with the current or, when necessary, pushed it forward by “setting” with a pole, in the short distance which the length of the stern deck permitted.

For the better footing of the captain in this process, as well as for drainage, the stern deck had a slight incline backward. The forward deck was even with the gunwale and the surface was slightly rounded, so as to shed the water.

The steering oar was thirty-three feet long, with a blade twelve inches in width, of the form shown in the plan. It is possible that the shape of the oar may have been slightly varied, according to the necessities of builders.

A “keel plank,” twelve inches wide, was a part of the hull, there being no keel. The boat, as a rule, was painted black and was without special name.

A movable mast, six inches in diameter and thirty-three feet long, with a boom of the same length and a three-cornered sail, enabled the boat to sail up stream when the wind favored. Being without keel or centre board, it could only sail with the wind astern, but, with a favorable wind, the progress was very rapid.

Sometimes the nature of the banks admitted of drawing the boat along by catching hold of the overhanging bushes, a process known as “pulling brush.” In Foul Rift, a particularly difficult rapid, the remains are still seen of iron bolts, in the rocky face on one side of the river, to which rings were attached, by means of which boats were drawn up by boat hook or rope.

In descending some of the rapids the “walking boards” were set up on edge as “splash boards,” to keep out the water which would dash over the sides. To admit of bailing out any water which might gain access to the hull, “bailing places” were provided at the ends of the decks. Water falling on the stern deck was carried below by a drain pipe.

The furniture was of the most limited character. A large iron pot, with a side hole near the bottom for draught, served as cook stove, with pieces of flat iron to hold the pan. There was a coffee pot and a water bucket and, for each member of the crew, a tin cup and plate and a knife and fork and, for all, the unfailing gallon jug of whiskey, from which, an old boatman stated, drinks were taken only at certain places. The men slept on “barn feathers” or straw in the forward cabin, when the weather did not admit of sleeping in the open.

Mr. Lugar, from whom these particulars were learned, wrote, “The Durham boat was the most beautiful modelled boat I ever saw. Her lines were perfect and beautiful. Her movement through the water was so easy, with such a clean run aft, that she left the water almost as calm as she found it. It appears they never could improve on the model of the original boat, as it was so perfect as far as light running was concerned. They could outsail any boat I ever saw sail, with a fair wind.

“Of course they could not work to windward, as they were too long and had no centre board. We could sail up any falls on this river. It took two men to steer them sailing up those awful currents, such as Wells’ Falls, Foul Rift, Cape Bush, Rocky Falls, Eagle Island, and many others.”

In the accompanying reproduction of a drawing made by the writer the form and dimensions shown are as indicated in a sketch by Mr. Lugar and confirmed by him, on inspection of the drawing. He was a skilled mechanic and possessed an excellent eye and memory for such details, and was very familiar with these boats, one of which he had owned and operated.

Mr. Lugar stated that in some details there were slight variations made by different builders. Some made the ends higher than indicated in the plan and the lengths varied from the usual sixty feet to as much as sixty-six, and, in the longer boats, there was sometimes the addition of a foot or two to the ordinary width of eight feet. Some observers recall seeing a much shorter length than sixty feet and boats having both ends precisely alike in curvature and sometimes not quite as sharp as indicated in the plan. Different statements have also been met with as to the exact curvature of the hull in cross-section.

In all essential particulars, however, the type was preserved, and, as Mr. Lugar pointed out, it was most admirably fitted for the service on the Delaware in which it was employed.

It is said that at one time there were several hundreds of these boats on the river. The largest fleet was at Easton, from which place were shipped large quantities of grain, whiskey and other products. At Coryell’s Ferry and Wells’ Ferry, now Lambertville and New Hope, a large number of boats were owned, these points being centres for a considerable population producing materials for transportation to Philadelphia. Many were owned at other points on the river.

A newspaper article relating to some conditions at Lambertville in 1796 states that at that time there were but few houses in the place and that the only means of transportation was a Durham boat which made a monthly trip between the place and Philadelphia.

A man now living informs the writer that he has seen as many as a hundred Durham boats laid up, for the night, at Lambertville, on their way up the river. In some recollections of the late John H. Horn, published a few years ago, he states that these boats would often go in fleets of as many as twenty-five, and that, in sailing in line, they made a beautiful sight.

One observer states that he has sometimes sat on the river bank and watched a number of Durham boats waiting for a favorable breeze, when a “puff” would suddenly come up and “off they would go like a flock of sheep.” Going thus in fleets the crews frequently aided each other, in getting through difficult places, by “doubling up.”

The life of the Durham boatman was very laborious. The descent of many of the rapids was attended with much danger, requiring constant vigilance, and the ascent of the stream was accomplished only by hard work. The crew must always be on the alert and they were subjected to severe exposure.

The boatmen were a strong and hardy set of men, and seemed to enjoy their laborious occupation. The Captain, feeling the responsibility of his position, bore himself with great dignity, especially on his arrival at port.

Regarding the use of the Durham boat on the extreme upper river, the following is found in a small volume by the late L. W. Brodhead, on the “History and Legends of the Delaware Water Gap,” published in 1857.

Mr. Brodhead says: “Long before any facilities, other than the rough wagon roads, were afforded the people, both north and south of the mountain, for the transportation of the products of the Valley of the Delaware to market, the old furnace at Durham on the Delaware, a few miles below Easton, had constructed, about the year 1770, a class of boats somewhat longer and narrower than the present canal boats and in shape somewhat resembling a weaver’s shuttle. The deck extended a few feet only, from stem and stern.

“The ‘captain,’ or steersman, stood on the stern deck, and guided the boat with a long rudder. A narrow planking on either side afforded a walking place for the pikemen, who, with long poles or pikes, propelled the boat up the current.

“These were called Durham boats and soon came into general use on the river. They were used as early as 1780, by John Van Campen, for the transportation of flour to Philadelphia, manufactured from wheat grown in the Minisink. Mr. Van Campen’s mill was at Shawnee, and stood near where Mr. Wilson’s mill is now located.

“In 1786 one Jesse Dickinson came from Philadelphia, and laid out a city in Delaware County, New York, called ‘Dickinson City.’ It was situated near what is now called ‘Cannonsville. Mr. (Dickinson brought his men and material up the Delaware in Durham boats. (Gould’s History of Delaware County.)

“The old firm of Bell & Thomas, at Experiment Mills, known for their energy and integrity, and pleasantly remembered by many still living, used the Durham boats extensively in their day, both in the transportation of flour to Philadelphia and in bringing up supplies for the neighborhood.

“The boatmen were a strong and hardy set of men, and seemed to enjoy their laborious occupation. The ‘Captain,’ feeling the responsibility of his position, bore himself with great dignity, especially on his arrival at ‘port’; and the boys who collected about the wharf, when the vessel hove in sight, were terror stricken at the imperious manner of the ‘Captain’ and the stentorian tones by which he commanded all alike, on board and on shore.

“After the completion of the Delaware Division of the Pennsylvania canal, the Durham boat began gradually to disappear, so that one is now seldom seen on the waters of the Delaware.”

Of the hundreds of these boats once on the river not one is now known to exist, so far as the writer has been able to ascertain, and he has succeeded in finding but one survivor of all the hardy men who, for so long a period, carried, by these boats, the products of industry to market and brought back the needed supplies. This man passed away before the completion of this account.

Articles on Durham Boats used in Washington's Crossing prior to the Battle of Trenton, 1776

Behind the Lines: The Durham Boat

History Net.com

Christmas Night, 1776: How Did They Cross?

Journal of the American Revolution

Washington Crossing the Delaware and the Durham Boats

Old Salt Blog

Archaeological study of a Durham Boat discovered in Lake Oneida, NY

Durham Boat – Defining a Vernacular Watercraft Type

by Ben Ford, Timothy Caza, Christopher Martin, and Timothy Downing, Society for Historical Archaeology, 2018

Provided here by permission.