African Americans in Colonial Durham

Enslaved Africans were present in the earliest European settlements along the Delaware, known to Europeans first as the South River. Swedish and Dutch settlers brought or obtained Black workers by the middle of the 17th century, according to transactional and criminal records as early as 1639. Once the British seized control the Pennsylvania colony recognized slavery in its laws and organizing documents.

William Penn himself and waves of English, Welsh, Scotch-Irish, Irish, and Dutch immigrants arriving after him kept enslaved Africans and their descendants. Via the thriving Quaker settlement in Barbados, Pennsylvania Quakers kept up a lively traffic both as keepers of enslaved persons and as slave traders in the early 1700s. Traders brought most enslaved Africans and descendants to Pennsylvania indirectly from Caribbean islands and other American colonies. Few landed directly from Africa.

From the outset followers of Quaker faith had reservations about slavery. Around 1750-70 the Quaker Meetings generally rejected traffic in and use of slaves and pressured slave-owning members to free them. Many settlers in Pennsylvania came from German-speaking areas of Europe, bringing with them a strong cultural and religious resistance to keeping slaves. Thus there was among many Bucks County settlers early on a built-in disaffection for the use of enslaved Africans. As such Pennsylvania had one of the lowest populations of enslaved Africans and descendants in the colonies.

Far more numerous than enslaved Blacks in Pennsylvania and the mid-Atlantic colonies were indentured Europeans, who paid off their passage to America in years of bonded servitude. As many as half of all 17th- and 18th-century European immigrants came to America under indenture.

Ironmasters . . . used slaves and indentured servants on their plantations. They typically hauled ore from banks to furnaces and plowed farmland. Slaves were a minority of workers on iron plantations; nevertheless, ironmasters were among the largest slave owners in rural Pennsylvania.

By the time of independence an estimated 11,000 persons of African descent lived in Pennsylvania, largely in the original southeast counties, of whom around half were enslaved. The number in bondage fell off progressively after passage of the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery by the Pennsylvania Legislature on March 1, 1780, the first such act adopted in the newly independent States. The Act immediately prohibited trade in and importation of slaves, but did not emancipate those already in bondage. Any new children of enslaved persons were to be given manumission at the age of 28. By 1840 all enslaved persons in Pennsylvania had died in bondage or were freed by manumission as stipulated in the Act.

Penn granted land to The Society of Free Tradesmen, which planned unsuccessfully for a mining and smelting operation in Durham in the earliest years of the Pennsylvania colony. It had in its charter a stipulation that slaves would be manumitted after 14 years. This policy was never implemented. The group of owners who organized the original Durham Iron Furnace in 1727, and their furnace managers, would have held slaves in lifetime bondage from the outset. While few specific records of this exist from early Durham, it can be inferred from records of similar iron furnaces and forges, dozens of which arose in Pennsylvania through the early- and mid-1700s. Durham was among the first.

Iron furnace masters were the largest slaveholders in the Pennsylvania colony. Most others generally kept only a few at a time. More affluent households, mostly in denser settlements in and around Philadelphia, held slaves in small numbers for domestic service. Pennsylvania farms weren’t suited to the expansive production of export crops like tobacco, rice, sugar, or cotton; as such they didn’t prosper on the forced labor of large groups of enslaved workers like plantations in the South.

As the first extractive industry European settlers undertook in Pennsylvania, iron operations immediately encountered a shortage of laborers. Early iron furnaces and forges occurred in remote areas, like Durham, having the required resources of iron ore, water power, and expanses of hardwood forest for charcoal production.

The ironmasters were especially vulnerable to the labor shortage because their dependence upon the forests for their fuel created small, relatively isolated, communities centered on the furnace and forge. They were remote from what labor markets existed along the coast and were unattractive to workers and their families, who preferred the greater social opportunities of urban areas. Ironmasters, therefore, turned to involuntary workers to fill much of their need for unskilled labor and sometimes for skilled as well. They used many indentured men, both white and black, and Negro slaves.

— Walker

Charcoal iron furnaces had to be organized as self-sufficient settlements producing their own food, fuel, shelter, tools, and other needs, often referred to as iron plantations. Free and indentured European workers, together with lesser numbers of free and enslaved blacks, provided the labor.

Ironmasters . . . used slaves and indentured servants on their plantations. Indentured servants typically hauled ore from banks to furnaces and plowed farmland. Bound servants often fled plantations, and soon after the American Revolution indentured servitude fell into disuse. Slaves were a minority of workers on iron plantations; nevertheless, ironmasters were among the largest slave owners in rural Pennsylvania. Ironmasters at [many] plantations did not pay wages to slaves, and all slaves were subject to being sold as property. Slaves had complex relationships with ironmasters and each other. Small numbers of slaves worked at iron plantations, so slaves usually had few others to turn to for mutual support. For the African-born, their different languages and unfamiliarity with English or German hampered communication. Slavery was a lonely sentence for most blacks, and many resisted their captivity.

— Stories from PA History

. . . workers in the Pennsylvania iron industry constituted a heterogeneous group. English, Welsh, Scotch, Irish, Scotch-Irish, German, native-born American, Negro, and occasionally Indian workmen must be included in a survey of those who produced iron or who assisted directly or indirectly in its manufacture during the period under discussion. The workers may be classified in a general manner as follows: (1) free labor; (2) indentured servants or redemptioners; (3) Negro slaves and freed Negroes; and (4) journeymen and apprentices. . . .

While Negro slaves and freed Negroes usually worked at menial tasks, at many ironworks they were skilled workmen. Few skilled Negro workers were found at the blast furnaces, but many were employed at the forges. At Green Lane, Durham, Martic, Pine, New Pine, Mount Joy (Valley), Charming, Pottsgrove, and others, they performed the skilled tasks of refining and drawing iron into bars.

When slaves became skilled workers, they were very profitable, for the ironmaster had only to feed and clothe them. They were treated very kindly and considerately in eighteenth century Pennsylvania as may be seen from the records of small sums of money and other gifts given them, especially at the holiday seasons. As was the case with indentured servants, there were occasionally some who became restless and sought their freedom by running away. Here again it was usually difficult to effect the capture and return the fugitives.

— Bining

Specifically referring to the Durham Furnace plantation:

The intermittent character of the work permitted the farmhands, who were negro slaves during most of the colonial period, to pursue their work on the farm near by in the interval of filling and drawing off the ore. When the iron was ready to be tapped, a horn was blown and the slaves presented themselves.

— Colonial Dames

A thesis has been proposed that Africans brought with them indigenous iron-working skills that existed in the areas of Africa from which enslaved persons were stolen. Charcoal-fired iron forging in particular as practised in Africa was technologically superior to techniques known in Europe at the time.

African skills in ironmaking were a universal characteristic of the populations raided for slave importation throughout the continent. Distinct areas for slave selection were chosen because of the known skills of blacksmiths, craftsmen, and farmers.

The genius of African ironmaking was its steel core, the technology of making a steel interior through temperature control in the smelting with tuyeres, tubes to induct air into the furnace to make it hotter, removing carbon. The product was higher quality than European steel of its time.

Transfer of technological techniques of African ironmaking occurred when slave workers were charged with making iron in the Americas. Slaves were often placed at work at forges, which more closely approximated the African iron experience than furnaces. Charcoal technology, which matched the experience of Africans, remained operative longer in furnaces which used slave labor.

— Libby

Whether persons of African descent employed or enslaved at Durham Furnace brought ironmaking talents with them is a question, like so many, with the answer lost to time. Slaves employed in iron work evidently showed proportionally greater inclination to resist and flee from bondage.

A fertile source of information about slaves in Pennsylvania is found in the numerous advertisements which appeared in newspapers offering rewards for the recovery of fugitives. It is not unreasonable to assume that the slave who planned and executed an escape was endowed with intelligence and ingenuity above the average; consequently, the subjects of these advertisements may not have been typical of all slaves. Nevertheless, it is of interest to discover that the slaves at the ironworks included men of skill and accomplishment, and that their scale of living was well above subsistence levels.

— Walker

Lack of experienced iron workers and unskilled laborers constrained the growth of early iron works across the colony. Recruitment to isolated iron plantations was difficult. Both indentured and enslaved workers were sometimes inclined to run off seeking a free life. One source suggests that the Durham Furnace operators in 1737 petitioned the colonial legislature for a waiver of duties charged on the import of slaves, to help alleviate the shortage of manpower. It is uncertain if this was granted.

Confirming the use of slave labor at the Durham Furnace is this anecdote, that appears in at least two historical accounts of Durham:

From Dr. John W. Jordan furnishes an interesting item, showing the varied existence of one of the Durham slaves called Joseph, or “Boston.” Born in Africa in 1715, at the age of twelve he was taken with a cargo of slaves to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was sold to a sea captain, who took him to England in 1727. In 1732 he was sold to the Island of Montserrat, and thence with a new master was brought to Durham Furnace, with ten other slaves. In 1747 he was living in the household of Squire Nathaniel Irish, and while there was married to “Hannah,” but his master hired him to a furnace in New Jersey. In 1752 he was baptized by the Moravians at Bethlehem, and his owner, John Hackett, of the Union Iron Works, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, in 1760 sold him for fifty pounds to the Moravians. He died on September 29, 1781. “Hannah” was born July 11, 1722, at Esopus, New York, and in 1748, with her son, was sold to the Moravians for seventy pounds. She died November 24, 1815.

— Colonial Dames

This account also confirms slave ownership by the Moravians, despite the general preference among German immigrants to reject having slaves. The following article enlarges on that:

Like most colonists, Moravians accepted slavery in the 18th century and even brought to the colonies slaves who were converted in their Caribbean missions. In the South, Moravians kept slaves and even segregated them in church services. In the North, some kept slaves but it was common for Moravians to buy slaves with the intention of freeing them or to allow them to buy their own freedom.

Saving a slave’s soul was a higher priority for many than freeing them. Black people — the free and enslaved — worshiped alongside whites in Bethlehem and Nazareth, where they were sacristans or held other church duties and shared the Moravians’ regimented lifestyle.

— Radzievich

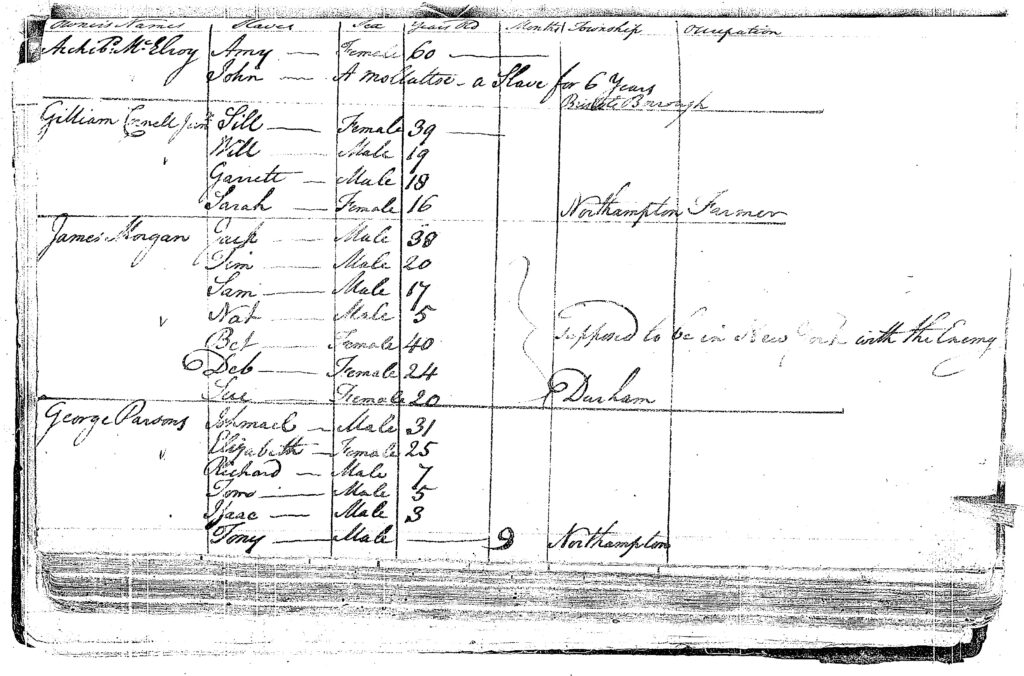

A stipulation of the 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery was that each county would maintain a register of all enslaved persons with the Prothonotary (i.e. County Clerk) by November 1782. In Bucks County 520 enslaved persons were registered in the initial document, Bucks County Register of Slaves, 1783-1830.

Through this document, we have one of the few written records of slave ownership in Durham. Two owners are listed, and both were involved with running the Durham Iron Furnace: one-time owner Richard Backhouse holding three enslaved females, and Ironmaster James Morgan. This was toward the end of Morgan’s life, who died in 1782. Seven individuals are listed as enslaved by Morgan, possibly an extended family: Jack, male 38; Tim, male 20; Sam, male 17; Nat, male 5; Bet, female 40; Deb, female 24; Sue, female 20. One wonders if the three women listed worked at the furnace or in Morgan’s household. Some historical evidence suggests enslaved women were employed next to the men in iron furnace and forge operations. Like all women at the plantation they would have worked in the farming fields.

An interesting story comes to us from James Morgan’s Slave Register entry. Next to the list of these enslaved people’s names is a bracket pointing to an annotation in the same handwriting: “Supposed to be in New York with the Enemy.” Referring to the Durham Furnace, the History of Bucks County states, “Twelve slaves were at work there in 1780, five of whom made their escape to the British at New York.” At another place in the same book the author states “six of the seven” fled to New York. It’s possible to interpret the bracket on Morgan’s Register entry of enslaved persons as indicating only six of the seven names.

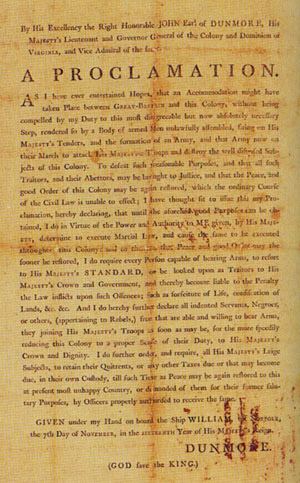

In the course of the American War of Independence British officials issued at least two statements encouraging enslaved Americans to flee their bondage and join the Loyalists. The first, Dunmore’s Proclamation in 1775, offered freedom to slaves who promised to join the fight as British soldiers. The second was the Philipsburg Proclamation of June 30, 1779, issued by British Army General Sir Henry Clinton from his temporary headquarters at the Philipsburg Manor House in Westchester County, New York. It declared all persons enslaved by American Patriots to be free and promised them protection and land if they left their masters, with or without commitment to join the fighting. These were the first mass emancipations of American slaves.

In the course of the American War of Independence British officials issued at least two statements encouraging enslaved Americans to flee their bondage and join the Loyalists. The first, Dunmore’s Proclamation in 1775, offered freedom to slaves who promised to join the fight as British soldiers. The second was the Philipsburg Proclamation of June 30, 1779, issued by British Army General Sir Henry Clinton from his temporary headquarters at the Philipsburg Manor House in Westchester County, New York. It declared all persons enslaved by American Patriots to be free and promised them protection and land if they left their masters, with or without commitment to join the fighting. These were the first mass emancipations of American slaves.

Such protection would have been realized in areas held by the British, like New York City. It is plausible to imagine a family or group of people enslaved at Durham fleeing to British lines, joining other “Black Loyalists.” At the end of fighting the British were generally good at their word. They transported thousands of escaped blacks from New York to British-held ports in Nova Scotia, the Caribbean, England, and elsewhere — removing them from bondage in America. From Canada many Black Loyalists moved on to a black colony organized by British abolitionists in Freeport, Sierra Leone.

Thousands of Black Loyalists escaped slavery, fled to New York, and subsequently got passage on British ships to Halifax Nova Scotia in 1782. Their names were recorded to facilitate compensation by the British of the Patriot slave owners from whom they fled. The record was called The Book of Negroes, transcribed and published in 1996 as The Black Loyalist Directory. There are no entries in the book recording escaped slaves from Durham, PA. There was, however, a record of one Samuel Flemming, “20, stout fellow. Born free, lived with James Morgan, Valley Forge, left him 5 years ago.” In the 1760s Ironmaster James Morgan had built a home in what is now Audubon, PA, just across the Schuylkill River from where the Revolutionary Army famously camped for a difficult winter during the war. Morgan had a lead mine there and possible interest in the Mt. Pleasant forge on Valley Creek, for which Valley Forge was named. This home later became the property of John James Audubon and stands today as a museum and nature center dedicated to the avian naturalist.

There were known cases of free Blacks in Bucks County and throughout the Colonies joining the Patriots to fight the British, though none of these were recorded from Durham. Some 5,000 Black Patriots fought against the British, usually within the ranks of white Revolutionary Army units. The status of escaped slaves throughout the War was fluid and confused. Some enslaved who fled from Loyalist masters were returned by the British with the expectation of leniency for escaping, while those who escaped from Patriots were protected. At one point Patriot leaders offered freedom to escapees who had joined the British and agreed to switch sides. On both sides there were cases of bad faith when Blacks who fled from bondage to a promise of freedom, either from the British or the Patriots, ended up being returned or sold back into slavery by the supposed liberators. All told, though, far more slaves fled their masters to join the British. As Simon Schama puts it in Rough Crossings, his history of Black Loyalists, “. . . the stark fact that the British were their enemies’ enemies made them keep coming to the royal standard. The majority of slaves wanted nothing to do with the new American republic of bondage.”

The earliest European settlers in Durham were engaged almost exclusively with the iron plantation, and so too were the persons of color they enslaved or employed. By 1780, isolated as it was and with a high proportion of German settlers, Durham was among Bucks County townships in the Register of Slaves with the fewest enslaved. Adjacent Springfield Township had none, while Northampton (then part of Bucks County) with a larger population of Dutch and Moravian immigrants, and comparatively large in area, had the county’s largest number of enslaved.

When enslaved persons achieved manumission some may have settled locally as freedmen. Unlike European indentured servants who often contractually received plots of land, sometimes livestock and tools, at the end of their service, freed blacks were mostly turned out with no resources to shift for themselves as best they could.

[T]he record is undeniable that for more than a century and a quarter the ironmasters of [southeastern Pennsylvania] placed great value upon their Negro employees, whether they were slaves, apprentices, indentured servants or free workmen. Some were exploited, and some were treated on terms of equality with white workers of the day, but, all in all, they played their part in the development of a vital Pennsylvania industry.

— Walker

The Durham charcoal furnace and forges ceased operations in 1791. Two generations would pass before a new, much larger anthracite iron works started up in 1848 on the banks of the Delaware, down Durham (Cooks) Creek from the original Durham Furnace. Durham iron workers of that later era likely included free people of African descent.

Sources

Bell, Herbert C. Durham Township. A. Philadelphia, PA, 1887.

Bining, Arthur C. Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century. Harrisburg, PA,1973.

Davis, William W.H. The History of Bucks County Pennsylvania: from the discovery of the Delaware to the present time. Doylestown, PA,1876 and 1905 editions.

Hodges, Graham Russell, The Black Loyalist Directory : African Americans in Exile after the American Revolution, 1995, New York, NY.

Libby, Jean: “Technological and Cultural Transfer of African Ironmaking into the Americas and the Relationship to Slave Resistance,” Rediscovering America: National, Cultural, and Disciplinary Boundaries Re-examined, Louisiana State University Dept. of Foreign Language and Literatures, 1993

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Website: Stories from PA History: The Pennsylvania Iron Industry: Furnace and Forge of America

Radzievich, Nicole: “Moravian record books hold little-known history of slaves,” The Morning Call, May 16, 2015, Allentown, PA.

Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the slaves and the American Revolution. New York, NY: 2006.

Turner, Edward R. Slavery in Pennsylvania. Baltimore, MD, 1911.

Walker, Joseph E. Article: Negro Labor in the Charcoal Iron Industry of Southeastern Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 93, No. 4 (Oct., 1969), pp. 466-486. Philadelphia, PA.

Wright, Richard R. The Negro in Pennsylvania, A Study in Economic History, Doctoral Thesis. Philadelphia, PA. Ca. 1900