The Durham Charcoal Iron Furnace, 1727 - 1789

The earliest European settlers along the Delaware river, Swedish and Dutch, made no attempts to mine or refine iron ore. Attempts at iron manufacture arose in nearly all the early English colonies during the 17th century, with the first in Massachusetts, Virginia, and Maryland. Often these attempts folded soon after starting. The first iron operations in Pennsylvania/Delaware started in the early decades of the 18th century. Some were forges, some bloomeries (a more primitive mode of iron smelting). Different sources cite Durham furnace, founded 1727, as the fourth charcoal blast furnace established in Pennsylvania. Starting in 1716 the earliest Pennsylvania furnaces began on tributaries of the Schuylkill River near present-day Pottstown and Phoenixville. There is evidence that an iron bloomery may have preceded the blast furnace at Durham by some years.

Tradition asserts that iron was made at Durham long before the works of 1727 were erected; and if this be true, it may safely be assumed that the blomary or stuckofen was in use for this purpose. The process of smelting was attended with much difficulty (owing to the crude process thus employed) and without the knowledge of chemistry. . . . The annual product of a blomary of this character was about one hundred and fifty tons. The weekly capacity of the regular furnace was twenty-five tons.

— Bell

Charcoal iron furnaces had a finite life span imposed by the availability of charcoal fuel produced from nearby hardwood forests. Furnaces consumed enormous amounts of wood. Once an area near ore sources was cleared entirely of trees a furnace became impractical to operate and the owners would shut down, sometimes moving on to a new site with available ore and timber.

Forges typically consumed between two and three hundred cords of wood per month for charcoal, while some larger furnaces needed more than one thousand cords per month to operate. Despite efforts at replanting wooded areas, most ironworks ran out of wooded lands in less than twenty years, after which they became dependent on local farmers for resources. Between one-quarter and one-third of the yearly workforces at Pennsylvania ironworks were engaged in cutting wood at least part-time.

— Kennedy

Between 1700 and 1800 over 60 different blast iron furnaces were established across Pennsylvania, with perhaps 20 operating at any given time. The same operators often ran several furnaces and forges in different locations, moving from one site to another. Iron forges were more numerous, some co-located with furnaces while others were customers of furnaces producing pig-iron.

In the late 1600s, William Penn (the Proprietor of Pennsylvania) granted important powers to The Society of Free Traders (a group of businessmen based in London). They were granted tracts of land in Bucks County near present day Doylestown, Warwick, New Britain, Hilltown, and Durham. “Durham” was laid off for the Society in the township that now bears its name. The Society was organized as a trading and manufacturing corporation. The Treasurer of the Society, James Claypool, wrote in 1682 . . . “We are to send out one hundred servants build houses, to plant and improve land, and for cattle, and to set up a glass house for bottles, drinking glass and window glass to supply the islands and continent of America as we hope to have wine and oil, some corn, hemp for cordage, and for iron and lead and other mineral . . .”

There is no doubt that the Society knew of the iron ore in the hills surrounding Durham. The record is silent on whether or not the Society was successful in mining or smelting the ore, but some iron production may have taken place on a modest scale with primitive and inefficient bloomery furnaces.

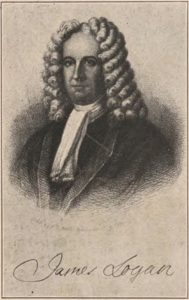

The known history of the Durham iron furnace dates from the year 1727 when a stock company was formed in Pennsylvania on March 4th. James Logan, William Penn’s original Secretary, having come to Pennsylvania in 1699, became the Proprietor’s chief American business representative, and a very successful businessman. His share of the stock issued by the new company was 25% of the total investment initially made. The other investors were Jeremiah Langhorne, Anthony Morris, Charles Reed, Robert Ellis, George Fitzwater, Clement Plumstead, William Allen, Andrew Bradford, John Hopkins, Thomas Lindsey, Joseph Turner, Griffith Owen, and Samuel Powell. This stock company purchased the Durham tract of land including the iron ore mining site from the Society of Free Traders.

These gentlemen were prominent and leading citizens: Jeremiah Langhorne became Chief Justice of the Province; he was a large land owner in Bucks County, including what is now Langhorne Park. Charles Read was a provincial councillor, later alderman and then mayor of Philadelphia, in which office he served three years, collector of excise, trustee of the loan office and judge of the admiralty court; his sister, Sarah, was the wife of James Logan. Clement Plumsted held many offices of public trust; he served as a provincial councillor, and three terms as mayor of Philadelphia; in 1741 he became entitled by deed from Robert Plumsted to the proprietaryship of East Jersey; William Allen (who married Elizabeth, daughter of Andrew Hamilton) was chief justice of Pennsylvania from 1751 to 1774, and the founder of Allentown; Joseph Turner, who for 50 years was a business partner of William Allen, served as a Provincial Councillor, and in 1745 declined his election to the mayoralty of Philadelphia. Among other interests these two gentlemen owned and operated the Union Iron Works in Hunterdon County, NJ., with its 11,000 acres of land, and the Andover Iron Works in Sussex County, NJ. James Logan, whose history is well known to you, was Penn’s secretary; Andrew Bradford was a printer, son of William Bradford, first printer of New York, and an uncle of the William Bradford so frequently referred to by Benjamin Franklin in his autobiography.

— Fackenthal

In the new country where there was a demand for iron for various purposes, the establishment of ironworks during the early years was limited by a lack of capital to erect such works and by the inability to obtain ready money to carry on such enterprises. A shortage of working capital was the chief obstacle to the development of the early iron industry. Few men who wished to engage in the manufacture of iron had the necessary money to do so. It was for this reason that groups of men usually combined to establish and finance ironworks. In an undeveloped country, suffering from a continual lack of capital, a relatively large amount of money was required to build and equip a plant for producing iron.

Almost all the ironworks, with few exceptions, were built and controlled by a number of partners, one of whom lived at the mansion house on the iron plantation and carried on the enterprise, being responsible for it to the company.

Much of the capital obtained for establishing ironworks was diverted from mercantile channels. Of the twelve original partners of the Durham Iron Works, six were merchants. Several members of the Potts family had stores in Philadelphia as well as iron plantations in the Schuylkill Valley.

— Bining

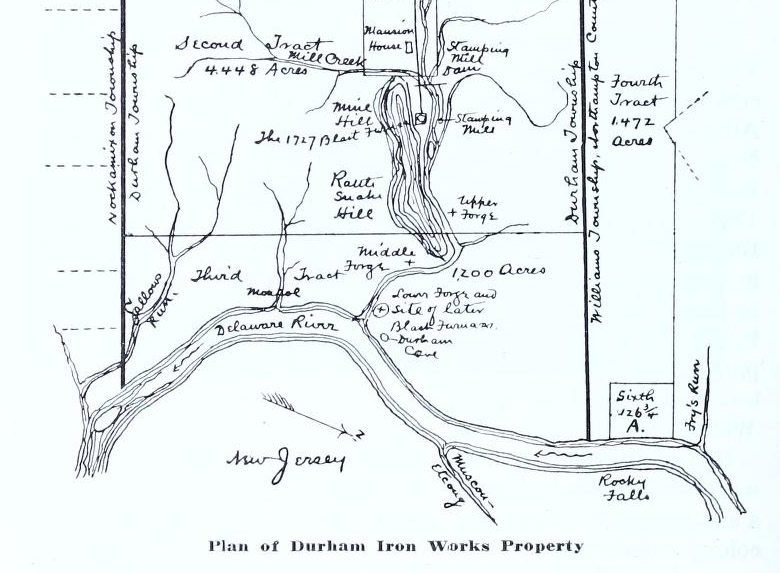

The first Durham furnace was built in 1727 and commenced operation in early 1728 on a stream about one and a half miles up from the Delaware, precisely where the present Durham gristmill now stands in the Durham Village center. This was to be the first industrial enterprise by Europeans in Bucks County and among the first in Pennsylvania. The water power of Durham (now Cooks) Creek that flowed past the furnace was used to operate the huge bellows that produced the blast, and a number of forges. The area was densely forested and a supply industry made the charcoal needed to fire the furnace. The charcoal burners’ work moved ever farther away from the furnace as forests were leveled to make fuel for the voracious iron furnace. Vestiges of the limekiln pits used to produce lime for the iron furnace are still in existence in Durham.

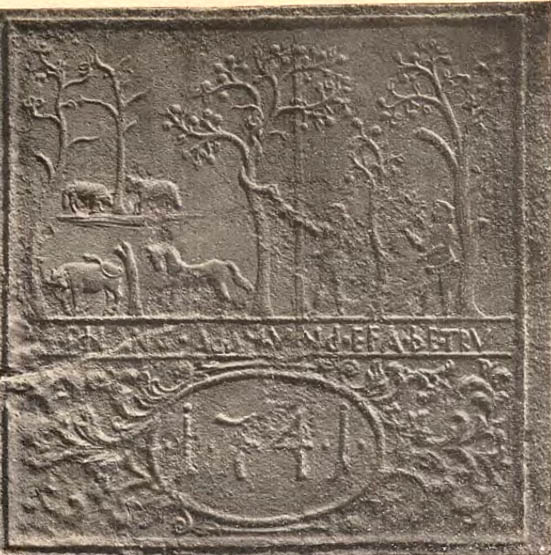

Britain was anxious to obtain supplies of iron for its industry. The forests needed to support large-scale conversion of ore to iron in Britain had been largely used up, so they were dependent on foreign sources and hoped the American colonies could provide a reliable supply. Durham Furnace exported three tons of pig iron (according to James Logan’s records) to England in 1728 as a sample but, at the same time, Russian and Swedish iron was being shipped to England at a lower cost. Thus, like other early Pennsylvania furnaces, Durham thrived on the production of finished cast goods for local consumption and bulk pig iron to supply local forges. They produced “hollow ware” like pots and pans; firebacks; stove plates; and munitions. A wood-burning stove similar to the famous Franklin Stove was produced in Durham in quantity. The “Adam and Eve” stove was manufactured in 1741 and onwards.

Once established, the Durham plantation had its own forges along Durham Creek and also supplied pig iron to client sites like the Chelsea and Greenwich forges in New Jersey. Ironmasters often rotated as lessees or owners between nearby production sites.

There is reason to believe that as early as 1734 there were two Durham furnaces. In Scull’s map of Pennsylvania (1759) an old and a new furnace and a forge at Durham are distinctly marked. In 1770 there were two furnaces and two forges at Durham. There were at one time three forges on Durham Creek.

— Swank

The wealthy, influential group of Durham Furnace shareholders were not directly involved in its operation. They leased the works to or hired ironmasters and managers to run it. One ironmaster was James Morgan. His father and grandfather immigrated from Wales and settled in Radnor, near Philadelphia. He was born in Durham in 1710. He traded in metal goods, was an ironworker in the early years of the forge and rose to ironmaster by the 1760s. In 1772 Joseph Morris, son of an original shareholder, sold his interest to Morgan, and subsequently Morgan obtained additional parcels of Durham land. It is believed he lived in a house along Durham (Cooks) Creek near the present day Red Bridge, where once a Brandywine creek flowed into Durham Creek. A neighborhood called Morgantown can be seen on old maps in that area. It is widely cited that James Morgan had a son, Daniel, around 1736 while living there. Daniel is said to have lived in Durham and worked briefly at the forge before leaving for the South. There he rose to prominence and General’s rank in the Continental army. This is not universally agreed to. Other sources say Daniel was born in Hunterdon County NJ to a poor charcoal burner named Isaac Morgan.

George Taylor immigrated from Ireland as a Redemptioner indentured on arrival to Samuel Savage, an owner of the Warwick furnace and Coventry forge. Taylor worked his way up from furnace filler, to clerk, and then manager as the owner became aware of his education and aptitudes. Upon Savage’s death in 1742 Taylor married Savage’s widow Ann and became the sole lessee of the Warwick works. In 1752 Savage’s son reached maturity and took control of the Warwick operation.

In 1755 Taylor leased the Durham furnace from the owners in partnership with another ironmaster, Samuel Flower. Taylor moved with his wife to Durham and assumed day to day operations of the furnace. He built his manor house close to the furnace. Today a house built in 1780, perhaps the oldest in Durham, still occupies the manor site where the first one burned down. Around 1755 Taylor is known to have supplied cannon shot to the Provincial government, “presumably for the French and Indian War.” When his lease on Durham Furnace ran out in 1761 Taylor moved on to ventures in Easton and built a grand house in what would later become Catasauqua near Allentown. The George Taylor Mansion remains today a National Historic landmark owned and operated by the Lehigh County Historical Society

A fire in 1768 destroyed “the combustible part” of Durham furnace, including the bridge house, casting house, and bellows.

The original Furnace Corporation created in 1727, and intended to continue fifty years, was dissolved by mutual consent before the expiration of that period. Most of the original partners had died, became insolvent, or sold their shares.

Among other gentlemen who later became shareholders in Durham Township and the iron works, were William Logan and James Logan, Jr., sons of James Logan; Judge Edward Shippen of Lancaster, Pa.; Lawrence Growdon of Trevose; Israel Pemberton, Jr., Langhorne Byles, James Morgan and James Hamilton. The latter purchased an interest in 1749 when serving as lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania.

On December 24, 1773, five years before the Durham copartnership would have expired by limitation, none of the original partners had survived. At that time Joseph Galloway owned four ninety-sixth of the company, and Lawrence Growdon of Trevose, who had owned fifty-eight ninetysixth, devised his interest to his two daughters, Elizabeth, wife of Thomas Nichelson, and Grace, wife of Joseph Galloway. That part of the property containing the iron works, mines and quarries was partitioned to Joseph Galloway in right of his wife, nee Grace Growdon.

— Fackenthal

Under Galloway the iron works were leased once again to George Taylor in 1774 for five years. Taylor by then had entered public life serving as a justice of the peace in Bucks and Northampton Counties. In 1764 he was elected from Easton to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. In 1775 he was reelected to the commission and attended the Provincial Convention. Taylor was among the signers of the Declaration of Independence and one of the few not native born.

In July [1775], as colonial forces prepared for war, he was commissioned as a colonel in the Third Battalion of the Pennsylvania Militia. On August 2, 1775, Taylor secured a contract with Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety for cannon shot. On August 25, with a shipment of 258 round balls weighing from 18 to 32 pounds each, Durham Furnace became the first ironworks in Pennsylvania to supply munitions to the Continental Army.

— Wikipedia entry on George Taylor (Pennsylvania Politician)

When Joseph Galloway aligned himself with the Crown and fled to join the British at New York, his estates were declared forfeited to the Commonwealth. The Durham property was confiscated in 1778 and sold to Richard Backhouse in 1779. George Taylor was able to complete his five year lease on the Durham Furnace. He then moved on to co-own the Greenwich Forge in New Jersey. James Morgan served Backhouse as ironmaster until his passing in 1782.

To his credit, Backhouse maintained excellent records of the iron works operations from 1778 to 1789, which were ultimately transferred to the Bucks County Historical Society where they remain today. Among other things, those records indicate that the iron works employed around 200 people annually during active months during the 1780s. Around 30% of these were seasonal or contract workers, especially among woodcutters, colliers, and mine helpers. “The total of 209 annual workers at Durham does not include an unknown number of sons, daughters, wives, etc. who helped cut wood, make charcoal, or engaged in other work attributed to listed employees.” It is estimated that the iron works drew labor from a radius area of 12-15 miles around the furnace. (Kennedy)

The number of workmen needed to operate the furnace was not large. Two founders, two keepers, two guttermen, two or three fillers, who filled the furnace with alternate charges of charcoal, ore, and limestone, a “potter” who made the hollow ware, an ore roaster, and a few laborers included them all. The “founders,” who regulated the furnace, made the sand molds, and cast the iron, together with the potter were the only skilled workmen employed at the furnace. Frequently the potter was an itinerant worker, working a few weeks at one furnace and then traveling on to another. As the work of ironmaking had to be carried on night and day, the workers labored in two twelve-hour shifts.

— Bining

In much greater numbers were woodcutters and colliers engaged with supplying timber and charcoal in vast amounts. Miners and miners’ helpers were another specialty — blasting, digging and hauling ore to the surface and on to the furnace. The forges employed skilled finers, chafery men, and hammermen who heated the metal in hearths and drew out the bars to given sizes under huge water-powered hammers. Lastly were the teamsters to deliver finished goods, and laborers, often including women. Laborers rotated between field work raising crops and assisting as needed at the furnace or forges. There is clear evidence of enslaved Black people working at the Durham iron plantation as laborers and possibly as skilled forgemen. For more on this see African Americans in Colonial Durham. A written record shows that in 1780 at least one German prisoner of war was turned over to Richard Backhouse “to manage, order, and direct as you think just and right.”

While many ironmasters prospered during the eighteenth century, a tragic phase of the Pennsylvania iron industry was the large number of failures. The problem of securing capital in sufficient quantities continually faced those who engaged in ironmaking. Beside this, the difficulties in obtaining cash payments for the iron sold; the problem of securing skilled labor; the locating of furnaces near poor ores, or where the supply ran out; the high cost of transportation from the plantations, a few of which were almost inaccessible before roads could be built; and mismanagement in the conduct of the business were causes, one or more of which led to the downfall of many ironmasters.

— Bining

Backhouse operated the Furnace with varying success until it blew out in 1791. Some sources cite 1793, when Backhouse died, as the year of the final blast. It seems certain that the decimation of nearby hardwood forests needed for charcoal contributed to the demise of the early Durham iron operations.

Mrs. Joseph Galloway (nee Grace Crowdon), died in 1782. Her trustees in 1803 succeeded in a suit against the heirs of Richard Backhouse (died 1793), who were dispossessed because of proof that Joseph Galloway, who devised his property to his daughter E. Roberts of London, held the property only in right of his wife, Grace Growden.

— Colonial Dames

Durham [was listed] as active in 1783 and producing 400 tons annually; and it is also listed by Samuel Potts in 1789 as producing the same amount. Backhouse got into financial trouble and tried to rent it in 1789 but apparently had no takers. It had 1,100 acres at that time. The original furnace was blown out in 1791 and torn down in 1820.

— Historical Society of Pennsylvania

In evident disagreement, Fackenthal wrote:

The last blast of the 1727 furnace was made in 1789. . . . The only part of the old furnace remaining is a stone arch in the bank where the stack stood.

The 1727 charcoal furnace covered a period of 62 years, from 1727 to 1789. The property then lay dormant for 59 years until the Whitakers bought it and built two anthracite furnaces in 1848-49. . .

The capacity of the charcoal, cold blast furnace of 1727, operated by water power and blown through one tuyere by a leather bellows, was not over 16 to 20 tons per week of seven days. Owing to the difficulty in supplying charcoal enough and because of freezing weather the furnace did not operate during the winter months, and moreover there were many suspensions and stoppages, the furnace frequently making several blasts during the same season. It is therefore not likely that the output of pig iron and castings averaged more than 350 gross tons a year over the 62 years of its life. This estimate is based on the known output for the years 1781 to 1789, and suggests a total of about 21,700 tons during its entire 62 years.

Sources

Bell, Herbert C., Durham Township, Philadelphia, A Warner & Co., 1887.

Bining, Arthur Cecil, Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, 1973.

Fackenthal, B.F., The Durham Iron Works in Durham Township, Read before the Friends Historical Association of Philadelphia, Buckingham Friends Meeting House, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, June 10, 1922.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Collection 212. Forges and Furnaces Collection, 1727 – 1921.

Kennedy, Michael, “Working Agreements: The Use of Subcontracting in the Pennsylvania Iron Industry 1725-1789,” Pennsylvania History vol. 65, no. 4, Autumn 1998, The Pennsylvania Historical Association, Scranton, PA.

The Pennsylvania Society of the Colonial Dames of America, Forges and Furnaces in the Province of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1914.

Swank, James M., Introduction to a History of Iron Making and Coal Mining in Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1878.

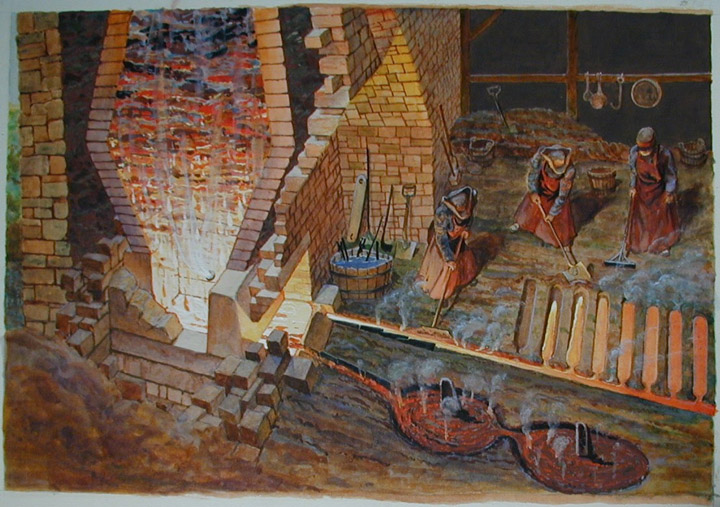

Charcoal Iron Furnace Operations

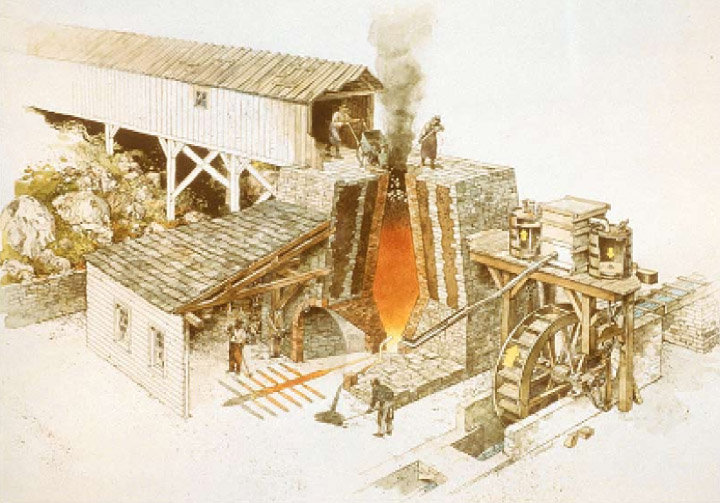

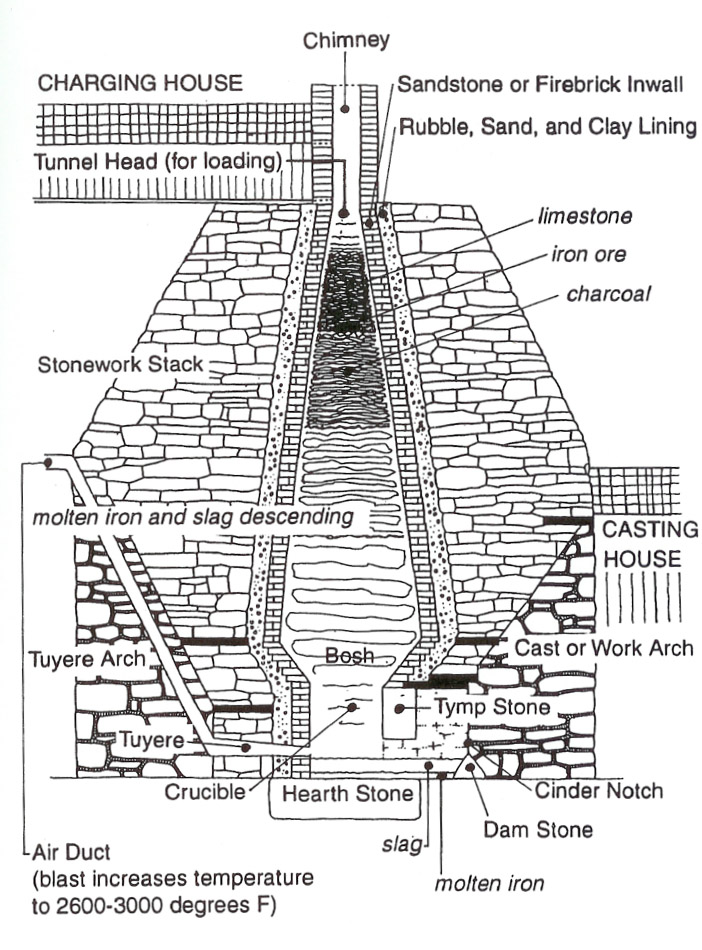

Artwork representing charcoal cold blast iron furnaces with the stack sectioned to show the fire. (Illustrations from National Park Service)

The furnace was filled from the top with layers of charcoal, iron ore and limestone. The heat and components triggered chemical reactions separating the iron from other compounds in the ore. Large leather bellows powered by the water wheel provided an air-temperature blast of air, thus the term cold blast, which helped the fire reach 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The furnace’s contents would shift downward and melt into iron and slag. Every 12 hours the furnace was drained. The molten iron flowed out into sand molds for finished-product castings or raw iron “pigs,” and the slag was discarded. This process ran continuously for months on end, only stopping when the furnace’s fire brick lining needed to be replaced.

(National Park Service)

As a rule the old furnaces were built into the side of a hill, in order that the ore, limestone, and charcoal could be filled from the upper level into the stack. Built upon one general principle, the charcoal furnaces varied materially in size and appearance. The interior of the furnace-stack was lined with a wall of fire brick, or else with fine-grained white sandstone, both of which were well adapted to resist the extraordinary heat to which it was exposed. The lining was constructed a few inches from the main stack, the space between being filled with fragments of stone, sand, and occasionally coarse mortar. This served to protect the stack from the decomposing effect of heat. The furnace stack was, moreover, secured from expansion by strong iron girders embedded in it. The quantity of material filled in the top of the furnace stack was measured and called a charge. There were two charges or heats in the twenty-four hours.

The iron, melted in the furnace and run into “pigs” in the sand bed, was not fit for other than casting use until it had been re-heated, puddled in a forge, and hammered into blooms. Puddling meant stirring and turning it with long iron bars in a small oven. In this way certain impurities were eliminated.

Two and one-half tons of ore, and 180 bushels of charcoal produced about one ton of metal. The output of iron was about 28 tons a week, as against the 75 to 600 tons a day produced by the modern furnaces [written in 1914]. The limestone introduced was for fluxing or eliminating impurities, and the quantity used depended on the richness or metallic content of the ore. “Before using the ore it was washed by a big water wheel attached to a long lateral shaft which had heavy iron teeth running around it spirally and which revolved in a trough. The teeth stirred the ore in the water and finally threw it out in a pile from which it was gathered up in a cart. Lumps of ore that were too large to wash were purified and reduced by burning. They were stacked in the oven, charcoal filled between, and the huge pieces heated enough to break them.” Besides the ordinary furnacemen, cast boys, miners, and colliers, there were two keepers who took turns of twelve hours each to watch the furnace, a master miner, a chief collier, and a manager.

— Colonial Dames

Life on Colonial Iron Plantations

Excerpt from Bining, Arthur Cecil, Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, 1973.

This text describes the lives of people on the dozens of Colonial iron plantations that spread across Pennsylvania before and after Independence. Durham was one of the first and carried on among the longest.

During the eighteenth century, the iron industry in Pennsylvania was organized largely on plantations. Many of these consisted of several thousand acres of land. The mansion house, the homes of the workers, the furnace and forge or forges, the iron mines, the charcoal house, the dense woods which furnished the material for making charcoal, the office, the store, the gristmill, the sawmill, the blacksmith shop, the large outside bake oven, the barns, the grain fields, and the orchards were part of a very interesting and almost self-sufficing community. In some respects, the iron plantations resembled small feudal manors of medieval Europe.

It is not strange that these plantations were of great extent. Much woodland was necessary for the thousands of cords of wood consumed annually in the form of charcoal by each furnace. Forges used much less, but still a relatively large amount, of fuel. Many acres were also needed for cultivating grain and raising the food required by the workers. Elizabeth plantation consisted of 10,124 acres, Durham of 8,511 acres. Boiling Springs of 7,000 acres, Reading of 5,600 acres, Martic of 3,400 acres, Warwick of 1,796 acres, Pine of 1,280 acres, and Thornburg of 1,200 acres.

The mansion house, where the ironmaster and his family lived, was usually built on a low hill overlooking the furnace or forge. The house was stately and commodious, with large rooms, wide, open fireplaces, and excellent furniture, often imported from Europe.

Site of the original Durham Furnace mansion house. (Now a private residence closed to the public.) The pictured house was built in 1820 to replace the original mansion that burned down. George Washington is reputed to have been a guest at the original mansion house.

In the east [of Pennsylvania] the cottages of the furnacemen, forgemen, miners, farmlands, and other workers were usually small stone structures or were built of log and plaster with stone chimneys. In the central and western parts of Pennsylvania, they were more often log cabins. All were poorly furnished. Until the end of the eighteenth century, rugs and carpets were unknown in the homes of the workers. Sanded floors and whitewashed walls often made for cleanliness. In the smaller houses, there were but two rooms with a loft above.

Just below the mansion house and not very far away from the dwellings of the workmen stood the furnace, a truncated pyramid of stone. Built into the side of a small hill in order that the ore, limestone flux, and charcoal could be put into the furnace at the top, it was an impressive sight when in blast. The intermittent roar of the forced blast could be heard a long distance away. From the top of the furnace stack a stream of sparks was occasionally emitted as the flames rose and fell. At night the almost smokeless flames cast a lurid glare upon the sky which was visible for miles around, and illuminated the surrounding buildings. Within the main casting house, or casting shed as it was called, which was built directly in front of the furnace, the “mysteries” of casting were carried on. Here the molten metal was run from the hearth into the waiting molds of scorched and blackened sand. Creaking wagons drawn by teams of horses hauled the iron ore up the furnace road. From the “bank,” the fillers carried their baskets of ore, limestone, and charcoal across the bridge to the furnace top. Pig iron was the chief product of the blast furnace, although pots, pans, kettles, stove plates, and firebacks were also cast.

The forge, where the pig iron was refined and hammered into blooms, or bars of wrought iron, was generally not far distant. The dull, unvaried turning of the water wheel, the irregular splash of falling water, the rhythmic thump of the hammer, and the droning sound of the anvil were a part of life on the plantation. “Within the forge, half naked human beings of strong physique swung the white-hot pasty metal from the hearths to the great hammers by means of wide-jawed tongs. Under the steady strokes of the hammers, amid showers of scintillating sparks, the forgemen drew the bar to given sizes.” Bar iron from the forges was used by blacksmiths to make tools, implements, and ironware of different sorts.

In the midst of the community was the ironmaster’s store. All the necessities of life of the workmen and their families were secured there. It resembled in many ways a large country store of the present time, carrying supplies of all kinds. Grains and vegetables raised on the plantation; flour ground at the mill; the meat of cattle and animals bred in the fields; axes, shovels, chains, and hoes made by the plantation blacksmith; sugar and molasses from the West Indies; rum from New England; and imported goods from old England could be purchased. Broadcloth, linen, flannel, and other varieties of cloth were kept, as well as shoes, deerskins, scythes, fireplaces, stoves, and castings. The workers depended upon the store for drugs and medicines. Jesuits’ bark or Peruvian bark and medicines called “purges” and “vomits” were obtainable. Even coffins and funeral supplies were bought at the store. The store was a necessity because of the distance to the boroughs and also because of the scarcity of money.

Almost all the iron plantations possessed a sawmill. Timber had to be prepared for erecting buildings and for other purposes.

Ironmaking was only a part of the work on the plantations. All the cereals—wheat, buckwheat, corn, rye, oats, and barley—were grown. Plowing was mostly done with horses; occasionally oxen were used. The system of cultivation was poor. Land was sown with wheat until it would bear wheat no longer, then with barley until barley would no longer thrive, followed by oats, buckwheat, and peas. The exhausted land was forsaken, and a new piece of ground cleared. Flax and hemp were cultivated to some extent, and sheep were raised, chiefly for wool.

While the workmen toiled at furnace, forge, or mine, the women in the homes spun thread and wove cloth on spinning wheels and looms. In haytime and harvest, the women and children turned out to work long hours in the fields. Days were appointed for husking bees, in which old and young participated. The women even did the harder farm work. They made hay, pulled flax and turnips, helped at threshing, reaped the grain, and in fact did almost all the harvesting.

The workers handled little money. The ironmaster credited his workers with the amount earned by them each day on one side of the ledger: on the debit side he made entries of merchandise and goods bought at the store. Likewise, the ironmaster often received in exchange for iron sent to Philadelphia barrels of rum, dozens of pairs of shoes, and other merchandise, which he placed in his store to be sold to his workmen.

As most of the iron plantations were some distance from the boroughs, settlements, and villages, the workers did not travel far. On many of the isolated plantations, especially during the first half of the century, they knew little of what was happening in the world outside. All their interests were bound up in their community.

The ironmaster often employed a tutor or an old schoolmaster to teach his children. The children of the workers did not have the opportunity of receiving the smallest amount of training, although occasionally those of the better-paid workmen obtained instruction from the schoolmaster. Frequently the clerk or bookkeeper at the plantation store, being fairly well educated, served as the teacher. The inadequate number of church schools, or even the neighborhood schools which developed later, were too far away from the plantations to be of service to those who lived there. This was true not only in the west, but also in the more settled southeast for most of the period.

Churches were too few in all parts of Pennsylvania during the eighteenth century. If five or ten miles away, church could be attended occasionally by traveling there on horseback or in wagons. Some ironmasters, like “Baron” Henry William Stiegel at Elizabeth, conducted their own sacred services. Many itinerant preachers called at the different plantations. through the forests from one community to another.

During the period under discussion, most of the inhabitants of Pennsylvania drank much liquor and strong drink. The ironmasters could afford sherry, Catalonia, Madeira, Frenclr and Teneriffe wines, Jamaica spirits, Bordeaux claret, and bottled porter. The workers on the plantations drank much rum, whiskey, gin, cider, and beer. Drunkenness among the furnace workers was common. It was for this reason that the legislature passed acts in 1726 and 1736 prohibiting the sale of liquors near the furnaces. There was always a shortage of founders and skilled workers, and it was imperative that the furnaces be attended continually, or serious damage might result from the furnace running cold, from explosions, or from other mishaps.

While the lot of the workers on the plantations was one of toil, they found some amusement and relaxation in occasional barn dances, corn huskings, and country parties. Once or twice a year some of them were fortunate enough to be able to travel to the fair held at the nearest borough. By virtue of their charters, the boroughs were allowed to hold a market each week and two fairs a year. The fairs became centers of attraction. General merchandise, supplies, and livestock were sold. Many people attended them, and there was much excitement and pleasure. Some went to make purchases: others planned a wild frolic. Horse racing, drinking, and gambling often prevailed.

The highways which led from the plantations to the outside world and connected the boroughs, towns, and villages were picturesque. Quaint signboards of taverns along the road, and of inns and shops in the boroughs and villages, added to the attractiveness of the natural scenery. The Three Crowns, King’s Head, Grayhound, Black Horse, Unicorn, Golden Eagle, and Swan were but a few. Every craftsman and shopman had his sign representing his calling,

Along these roads and highways, long before the middle of the eighteenth century, the famous covered wagons which later played so great a part in the westward movement were transporting merchandise, goods, and produce to and from Philadelphia, and between the boroughs and towns. These “freight wagons,” or Conestoga wagons as they came to be called, were strongly built, the body sloping forward very slightly. They were covered with coarse cloth stretched over hoops. More than 7,000 were in use by 1750. Pig iron, castings, and bar iron were hauled from the furnaces and forges in heavy open wagons over tortuous roads to the main highways. The cost of transportation under these conditions was exceedingly high.

Those plantations which were not far from the rivers could send their iron and produce to market by water. The Schuylkill River was used to some extent, but difficulties in navigation prevented its extensive development as a waterway during this period. Iron was sent from Durham down the Delaware River to Philadelphia in [Durham] boats.

Many ironmasters imitated the life of English gentry. In the New World there was more isolation, perhaps, than in England, but the Americans enjoyed the advantages of hunting, fishing, and building fortunes that only a virgin country could give.

Life on the iron plantations, however, was cheerless at its best for those who had to toil hard and long. While the ironmaster could secure many luxuries, could afford to travel, even to Europe occasionally, and was able to provide teachers for his children, the lot of the workers was indeed very hard. There were few material comforts of life. It was a time when houses were lighted with tallow candles, when water had to be carried from springs or drawn from wells, when only a few had the opportunity of even an elementary education, when medicine as commonly practiced was a formulated superstition, rather than a science, and doctors purged and bled their patients. The few who traveled did so on horseback or in jolting stagecoach or springless stage wagon, over rough limestone or poor clay roads. On the other hand, stark poverty was unknown on the iron plantations, in spite of periods of occasional depression. The wages of the skilled workers were relatively high when compared with wages paid in European countries of the same time. Initiative, industry, and aggressiveness reaped rewards, for a number of ironworkers by hard work and constant application became ironmasters themselves.