The Durham Gristmill

The Durham Mill is an important historic gristmill located in Durham Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. With a rich and varied past that spans four centuries, the Durham Mill and Furnace has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1976. (See the 1976 nomination and acceptance form to the National Archives registering the mill on the National Register of Historic Places.)

Built in 1820, the Durham Mill was erected on the foundation walls of the original Durham Iron Furnace. The furnace, which previously operated on the site from 1727 to 1791, produced equipment for the Colonial Army, among other things. Colonel George Taylor (c. 1716-1781), a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was one of the furnace’s first managers. General Daniel Morgan, famed for his leadership in the Revolutionary and French & Indian Wars, is also believed to have worked at the furnace.

The Durham Post System was also established during this early period (c 1723), reportedly by the founders of the Durham Iron Company. The Durham Mill has housed the Durham Post Office, the nation’s second oldest, in its warehouse since 1912. The post office operates in the mill to this day.

History of the Mill

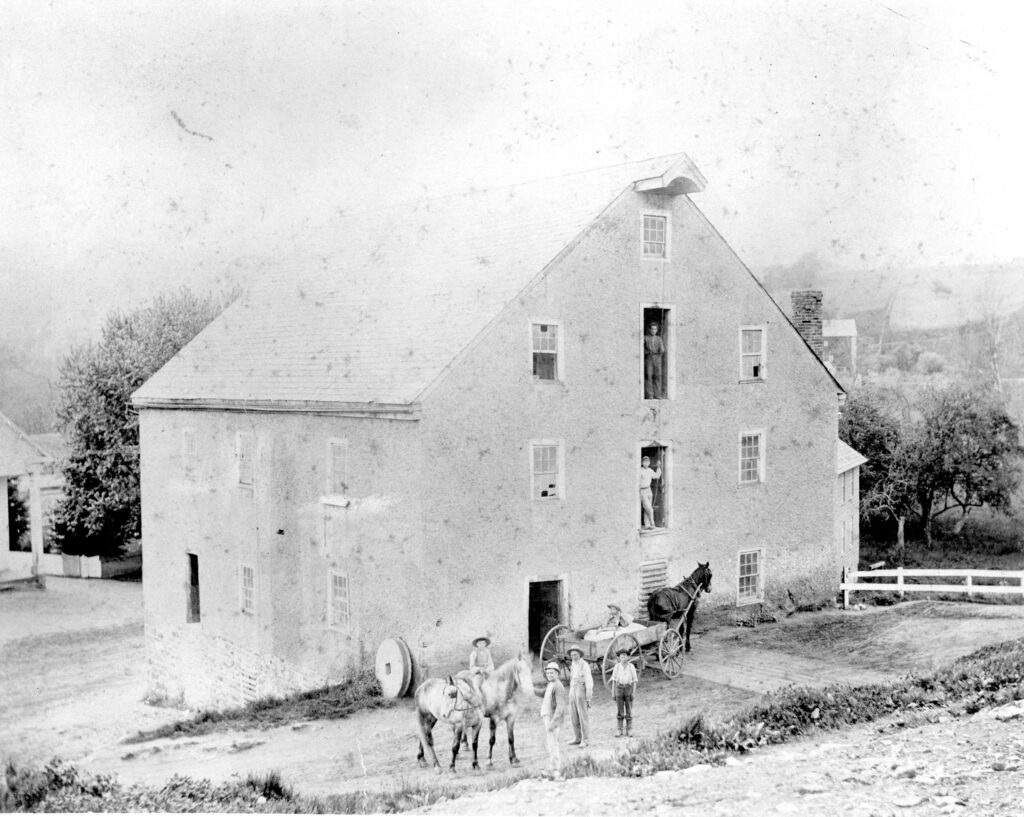

Erected by Judge William Long, the Durham mill was in operation for 147 years (1820-1967). During this time, the mill used the same fast-flowing water power from local streams that previously helped operate the furnace forges and bellows. The large water-wheel ground grains (such as corn, millet, oats, rye, barley) into flour and other products like livestock feed for local and domestic consumption. Grains were sold or bartered, with farmers paying what was referred to as a “toll” (or portion of product in payment) to the miller if bartering. Consumers ranged from nearby farmers and families to companies like the Ceresota Flour Company.

Pulling directly up to the mill for loading and unloading, trains on the local Q&E line (Quakertown & Eastern, a.k.a. the “Quick & Easy” by locals) transported shipments until the line closed. After this time, deliveries were made by truck.

Ownership

Although the gristmill changed owners many times, the mill did not cease operating between its opening in 1820 and closing in 1967. Towards the end of this period, the mill produced largely animal feed.

Former owners included Judge and Mrs Long; the Riegel Family; the Bachman Family (including Rubin Knecht Bachman, a U.S. Representative during the Hayes administration); John J. Mulford; and Harvey Lee Barber. A review of available deeds and maps shows the following points or transfers of ownership:

1820 – builder/owner: Judge and Mrs. William Long

1850 (map) – owner: D. Riegel

1867 (deed) – transfer of ownership from John L. Riegel to David Bachman

1888 (deed) – transfer of ownership from Rubin K. Bachman (son of David) to George H. Riegel

1891 (map) – owner: George H. Riegel

1892 (deed) – transfer of ownership from George H. Riegel to John J. Mulford

1892 (deed; dated 5 days after previous deed) – John J. Mulford to Harvey Lee Barber

1893 (deed) – transfer of ownership from Harvey Lee Barber to George H. Riegel

1901 (deed) – transfer of ownership from George H. to Harvey K. Riegel

1943 (deed) – transfer of ownership from Harvey K. to Clarence L. Riegel

1946 (deed) – Clarence L. to Vera B. Riegel (owned until 1970s)

The mill is now owned and administered by Durham Township.

Mill Construction

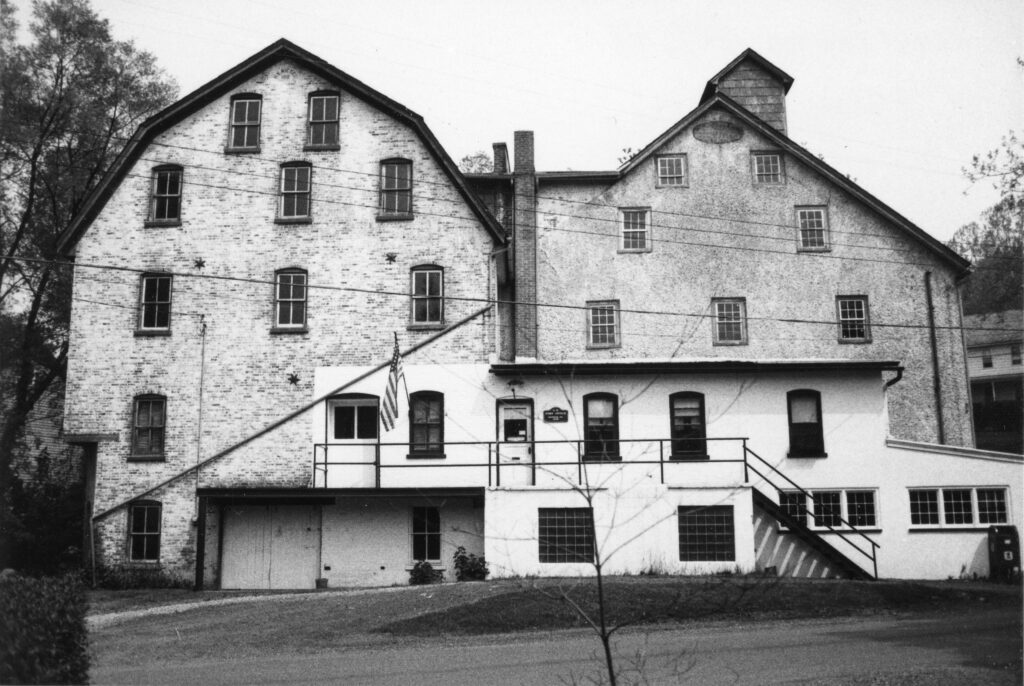

The Durham mill was initially built as a three-story stone building. Laid out according to the precepts of Oliver Evan’s The Young Mill-Wright’s and Miller’s Guide, the mill is typical of early 19th century gristmills found in Eastern Pennsylvania. It is constructed of stone rubble laid up on the old furnace foundations and then parked with a whitewashed crude stucco.

In the late 1800s and early 20th century, the mill expanded in structure and operation as custom and batch millings shifted to commercial scale flour and feed production. After taking over the mill in 1888, George Riegel built the barn and wagon shed (northeast of mill) to house and stable the horses and wagons.

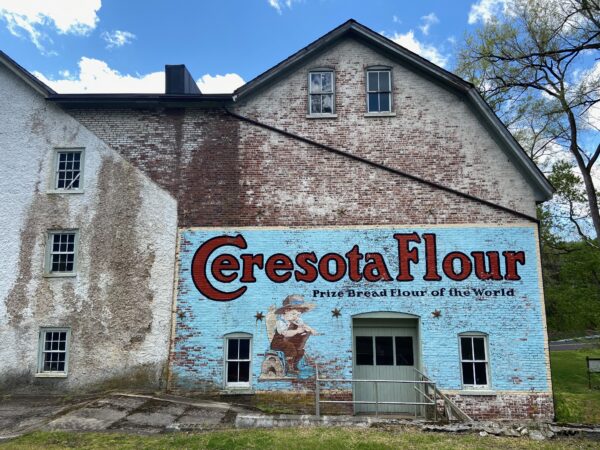

A large, 36′ x 63′ brick annex was added in 1912 by Harvey K. Riegel. Harvey Riegel had previously owned the wheel-wright shop and blacksmith shop that was annexed to the north wall of the mill and subsequently destroyed to make way for the new addition. The demolition of the second Durham anthracite iron works, located a few miles away, provided the bricks used in the construction of the 1912 annex. Adjoining the 40′ x 50′ mill, this gambrel roofed brick warehouse more than doubled the size of the mill operation.

The post office was constructed (north corner, west wall of mill) at this time as well, and housed both the post office and the mill office. This space was subsequently enlarged and a separate, adjacent mill office was created in the 1940s. The post office remains in operation today at the street level, and the old mill office now houses the Durham Historical Society.

Both the mill and annex are post and beam with timber and plank interior. While the mill has experienced heavy use from centuries of grinding service, the newer warehouse is in good condition internally and externally.

For more information on the architecture of the mill, extracted from an Historic Structure Report completed for Bucks County Commissioners and Parks Department by Jenkintown architects Hottle and Kwait in June 1975, please click here.

How the Mill Worked

A mile-long “mill race” channeled water from Cooks Creek (formerly known as Durham Creek) to the mill pond. To ensure adequate water supply, the miller operated a dam system at the top of the mill race which could be accessed as needed. The waterwheel was the source of the mill’s power. The original wooden wheel measured 12′ x 10′. In 1932, it was replaced by a 16′ x 8′ steel wheel with a 30 horsepower rating. Connected to a metal rod that ran through each floor of the building, the wheel powered a system of machines and pieces, including four mill stones, that could be engaged or disengaged as needed, even while the mill was running. The water wheel continued to be used daily, however eventually most grinding was done by electric power. Risks associated with the use of electricity, coupled with the high flammability of flour dust, resulted in the use of nearly all wood products to prevent fires. Chamfered edges were also used on wooden posts and support beams towards this end.

Raw product was hoisted to the top floor of the mill via a pulley-hoist system, where it was cleaned using a grain cleaning device known as a separator. After this the grain was transported down to a lower floor by an elevator system, where it was ground by the mill stones.

Mill stones were large and round, and ranged from 1.5-5 feet in diameter. Each could weigh up to 2,400 pounds. The larger the mill, the more stones it needed. Smaller mills needed one pair, whereas larger mills of the time period had up to 6 pairs. The Durham mill had 4 pairs, of which at least one pair were “buhr” stones imported from France and used for higher quality grain. Once milled, the product was conveyed back upwards to go through a finer sifting process. Finally, the ground and sifted grain was moved to a packing area where it was loaded in bags and barrels and prepared to be sent off to its destination.

Further information about the mill’s history and operations can also be found here.

Oral History of the Durham Gristmill

The following are memories recounted Ms. Lorretta Dysher in 1938:

“Grandfather Riegel had a large grist mill in Durham, PA. In the basement of the mill was a huge water wheel. This wheel was powered by water flowing over its paddles from the race across the street. I could look through a screened window and watch the wheel as it went around and around on its endless journey. I was fascinated by this wheel. It made me spellbound to watch and listen. The water flowing over the wheel made an eerie sound as it fell back into the dark waterway below. The continual motion of the wheel kept a cool breeze coming from the window, with a dank, musty aura.

“Upstairs in the mill were the various sized mill stones. These stones ground the flour and feed. Dad didn’t allow me in the mill very often. It was an extremely dangerous place for children to be. When I was permitted to enter the mill, I had to be very careful. Chutes crisscrossed throughout the mill. Some you could squeeze past, others were so low if you forgot to duck your head, a nasty goose egg would result. A massive system of belts and gears powered by the water wheel made the huge stones roll around and around. Underneath these huge heavy rolling stones, corn, millet, oats, rye, barley and grandfather’s Special Winter Wheat were ground. As varieties of grains were crushed, a delightful pleasant aroma shrouded the mill. Wet molasses was the best fragrance of all as it was added to the cow feed.

“Grandfather’s flour was always in demand. He sold his flour to customers locally, and as far away as Philadelphia and New York City. You could travel for miles and miles and everyone knew of its excellent quality. Grandfather’s flour was bagged in white paper sacks, with a piece of twine tying the bag shut. The front of the bag carried a picture of a young boy slicing a piece of homemade bread. Grandfather had this same huge advertising logo on the front of his mill. The young boy was sitting on a three-legged stool. He had on a big yellow straw hat and a pair of blue overalls with one strap unbuttoned. He had a bread knife in his hand ready to slice a piece of homemade bread. I loved to watch for this painting to come into view as we approached Durham and grandfather’s mill.

“In the morning dad would hook the combine to the tractor. The combine was a new machine for us. It cut the wheat and shook the grain from the stalk. The grains of wheat went up the auger and spilled into a waiting bag. My brothers stood on the machine’s platform. As a bag filled with wheat the boys would quickly tie it. Our hired man Milt took the full bag away and put an empty one in its place. When the platform was full they stopped the equipment to unload. Our team of horses, Dan and Maude, pulled a wagon over to the combine and the men transferred the full bags. The straw fell from the back of the machine. It laid on the ground for a day or two to finish drying. Then the straw was taken to the straw mow to be used as bedding for the animals. It was fun to watch the combine but it was hot, dirty, dusty work. By the end of the day my brothers would be black from head to toe.”

For more information on the mill’s operation and history, or to participate in a tour, please contact the Durham Historical Society.

The Durham Historical Society is raising funds to renovate and restore the mill to operating condition. Any donations are gratefully received and applied towards maintaining this important historical site. Please see our donation form, or visit our GoFundMe page.