History of the Durham Furnace and Ironworks

In the late 1600s, William Penn (the Proprietor of Pennsylvania) granted important powers to THE FREE SOCIETY OF TRADERS (a group of businessmen based in London, England). They were granted tracts of land in Bucks County near present day Doylestown, Warwick, New Britain, Hilltown, and Durham. “Durham” was laid off for the Society in the township that now bears its name and which was later sold to the Furnace Company in 1727. The Society was organized as a great trading and manufacturing corporation.The Treasurer of the Society, James Claypool, wrote in 1682 . . . “We are to send out one hundred servants build houses, to plant and improve land, and for cattle, and to set up a glass house for bottles, drinking glass and window glass to supply the islands and continent of America as we hope to have wine and oil, some corn, hemp for cordage, and for iron and lead and other mineral . . .” There is no doubt that the Society knew of the iron ore in the hills surrounding Durham. The Indians had long before advised the Europeans that they were mining lead in the hills and using that material for trade with other tribes and in the implementation of utensils. Whether or not the Society was successful in mining the ore or in it’s smelting, the record is silent but may have taken place on a modest scale but with primitive and ineffective smelting furnaces. There was no record of a furnace in Durham when the stock company was formed in 1727.

The recorded history of the Furnace dates from the year 1727 when a stock company was formed on March 4th. James Logan, William Penn’s original Secretary, having come to Pennsylvania in 1699, became the Proprietor’s chief American business representative, and a very successful businessman. His share of the stock issued by the new company was 25% of the total investment initially made. The other investors were Jeremiah Langhorne, Anthony Morris, Charles Reed, Robert Ellis, George Fitzwater, Clement Plumstead, William Allen, Andrew Bradford, John Hopkins, Thomas Lindsey, Joseph Turner, Griffith Owen, and Samuel Powell.

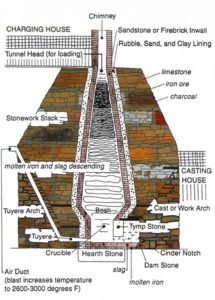

The first furnace was put in operation in 1727 in an area about one and a half miles up from the river precisely where the present gristmill now stands (built in 1820 on the ruins of the furnace) in the Durham Village center. The water power of the creek that flowed past the furnace was used to operate a number of forges and in working a huge bellows that produced the blast.

The area at that time was surrounded by trees and an industry quickly started up associated with the making of charcoal. The charcoal burners work ever moved farther away from the furnace as forests were leveled for the purpose of making charcoal for the voracious Durham furnace. Limekiln pits are still in existence in Durham the erectors of same long gone, as is the industry associated with their use and the art of charcoal making.

The Furnace exported three tons of pig iron (according to James Logan’s records) to England in 1728 as a sample but, at the same time, Russian iron was being shipped to England at a very low cost. The Americans could not meet the competitions cost. Labor was costly and the expense of shipping product down the Delaware River to Philadelphia was great. Slaves were used at the Furnace from 1727 through the close of the century but not extensively and some that worked there quickly made their escape to the British in New York.

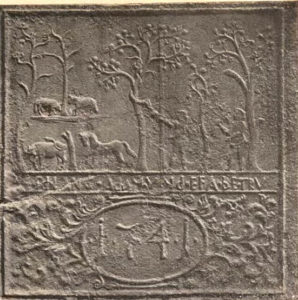

Important product was produced at the Furnace. A stove similar to the famous Franklin Stove was produced in Durham in quantity. The “Adam and Eve” stove was manufactured in 1741 and onwards. George Taylor, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, had an elaborate model of the “Adam and Eve” stove made with the inscription “DURHAM FURNACE 1774,” the year in which he came into control of the Furnace for the second time. The Furnace also produced shot and shell for the armies of George Washington during the War for Independence.

The original Furnace Corporation created in 1727, and intended to continue fifty years, was dissolved by mutual consent before the expiration of that period. The Furnace, its plot of ground and all its buildings, were transferred to Joseph Galloway and his wife Grace (12/24/1773). Mr. Galloway became the first individual proprietor of the Durham Furnace. When he aligned himself with the Crown and, joined the British at New York, his estates were declared forfeited to the Commonwealth and Richard Backhouse became its owner for a short period of time. However, the courts later concluded that Grace Galloway had succeeded to ownership and thus the properties were not subject to confiscation despite the fact that Joseph Galloway had joined the British cause, departed the colonies and was thus accused of high treason.

During the period of the Galloway heir ownership, the operation of the Furnace was entrusted to lessees or superintendents. James Morgan, Iron Master, was one of these. His son, Daniel Morgan was born in Durham, worked with his father at the Furnace, and eventually became the famous General Daniel Morgan in the Revolutionary War and founder of the brigade known as “Morgan’s Riflemen.” George Taylor, signer of the Declaration of Independence, originally indentured to one of the furnace lessees (a Mr. Savage) when he first arrived in the Colonies worked his way up from “filler” to “clerk” and ultimately as a member of the firm. Upon the death of his employer, he married the widow of the owner and became the sole lessee of the Works. His house still stands just outside of the Village Center of Durham.

The iron ore found in the hills of Durham was not of first class quality and the location of the Furnace vis-à-vis higher quality ore and good transportation lead to its demise, and thus ceased operation in 1791. Immense piles of bomb shells were removed from the premises in 1808 and the deserted buildings were allowed to decay. They had provided jobs for several generations of furnace workers, miners in the Durham hills, its various forges and transportation as well as other support services—blacksmiths, boatmen, food suppliers etc. . . . All gone . . . not needed anymore. A gristmill was built on the Furnace’s site in 1820.

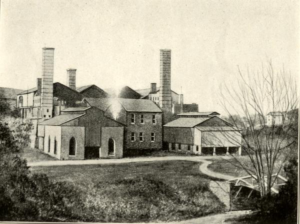

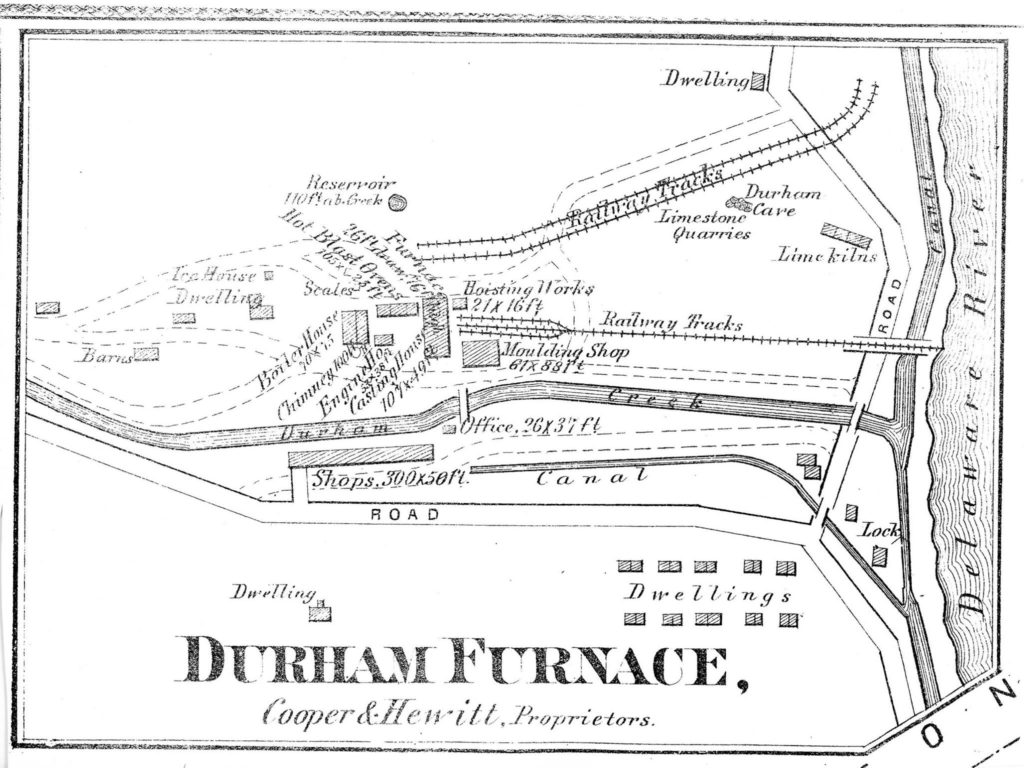

The Furnace business was not yet over in Durham interestingly enough. Two new furnaces were built in 1848-50 both of which were designed to operate with anthracite coal, charcoal now being much in disfavor and considered inadequate for the process.

Once again the odors and clamor of iron making resounded in the Durham area. The two blast furnaces continued to operate until 1874 at which time they were demolished and yet another furnace was put into blast in 1876. Coal for these furnaces was brought into Durham on boats from Mauck Chunk via the canals. Limestone was still quarried in Durham. Records reflect that three-hundred and fifty men and boys were employed at the Furnace from 1849 onwards. Only thirty-four percent of the ore was mined in Durham because of the low quality and the balance had to be brought in from New Jersey and mixed in with the Durham lot. Maps of this period illustrate extensive rail networks for the bringing in of raw material and coal and to remove product and slag. It was estimated at the time that the slag and cinder output amounted to one-hundred tons every twenty-four hours. This is a monumental amount of material that needs to be disposed of. Much of it was dumped around the Furnace, on the northeast end of Rattlesnake Hill and down by the Delaware River.

Steel making is an art that continuously improved over the years. Crude iron was developed by the Egyptians 2300 BC. Steel was identified in China about 1000 BC. The crucible process came into being in 1740 and the Bessemer process in 1855. The electric furnace was introduced in 1890. In Pennsylvania, Bethlehem steel became the “King of Steel” and the process at Durham faded into obscurity . . . but it was here in beautiful Durham in 1727. The odors, the clamor, the requirement for horses and mules and men and boys working at risky and dangerous jobs are memories of yesteryear that will live on as part of Durham’s history.